Recently I’ve been looking at a number of awesome blog posts that contains some great tips for writing more quickly. I got to thinking about how this might apply to myself and my students. And I realised most students actually do know how to write extremely quickly – if I had a dollar for every student I saw who wrote their entire essay in the 24 hours before it was due, I’d be very rich, very rich indeed.

So, when pressed, most students can write extremely quickly and this last minute speed writing becomes their modus operandi. But be warned, biblically speaking, what’s permissable, isn’t always beneficial. If I also had a dollar for every student I had crying, overwhelmed and melting down because they’ve left all their assignments to the last minute I would be even richer.

Most of the time writing is not very fun especially when these writing tasks have been externally imposed, appear to bear absolutely no relevance to your life and when you have countless options in front of you that seem infinitely more desireable than writing. The trick then, is to work out a way to get your writing done without losing your sanity. The way that I do this is by writing a little bit and doing this often.

In February this year, I had written a little over 20000 words on my thesis and by May, I had almost doubled that amount simply by doing a little bit and doing it often. I set myself a goal of 500 words per day and committed to writing 4 days per week. I kept a log of my daily progress and made notes to myself about what I needed to address or think about the next time I started writing. Things I found useful about this approach:

– I had a clear and quantifiable goal of what I was going to do. So often students set themselves intangible goals without breaking down that goal into the specific tasks. Eg. “My goal is to finish my whole assignment today.” and “I’m doing my research on Thursday.”

– I knew when I was finished. By doing a little bit every day, I felt absolutely no pressure to write more than 500 words in a day. Often, I did write more than 500 words but I felt absolutely no guilt about stopping once I had met my goal

– I could track my progress. By keeping the journal, I could see exactly what I had done and when. I felt motivated by my progress and inspired to keep going

– My stress levels went way down which was good for me and my family.

– I wrote more in 3 months than I had written in the 18 months prior to starting the journal

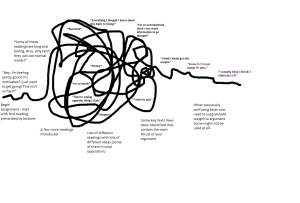

Often when I suggest this approach to students I am met with the following:

“I just work better under pressure.” (Subtext: “I do my assignments at the last minute and can still pass doing it that way.”)

“I’m just so busy – I can’t set time aside every day.” (Subtext: “I have better things to do.”)

“I just don’t work that way.” (Fair enough – different things work for different people but my question is always, “How do you work then?”)

“It just takes me so long to write!” (This is a very common one. My response: Rather than setting a word goal, set a time goal. There are some great apps that can help facilitate this. Also, it is takes you so long to write, isn’t it better to start earlier and do a little bit at a time?)

My favourite of these responses is most certainly the ‘busy’ excuse. Unfortunately, most of us are extremely busy and when people use their busyness as an excuse for not doing something to another busy person…well, it doesn’t really fly. I also think of my amazing and inspirational colleague who wrote her entire PhD in a year whilst working full time with a 2 year old at home: if that’s not busy, then I don’t know what is.

So, when it comes to writing, my suggestion would be to write a little bit and write often. Yes, you may be able to write your entire assignment in one day but is that really the best idea? Do you actually like staying up all night, living out of vending machines in the 24 hour lab at uni and being overly emotional and irrational? Set yourself a goal you know you can achieve and stick to it. It’s just like exercise: nobody ever really wants to do exercise but after they’ve done it, they feel better for it, and nobody ever regrets doing exercise! Same principle applies here. I’ve included some photos from my journal so you know I’m not lying and that I do practise what I preach!